Andrey Soloviev

0. Intro

As late as recently our musical culture gave birth to a lot of myths. To a certain degree, it is connected with the fact that at each stage of its development one can find some hidden layer, a focus of attention, not completely reflected in documents and artifacts. One of such enigmas is avant-garde jazz of pre- and post-perestroika periods. Notwithstanding that this phenomenon was developing during the hi-tech era, many of its key events had not been recorded on video or audio media. While witnesses of those short and wild times are still alive, such circumstance is taken for granted. However, in the nearest future, the history of the Moscow alternative scene of the 80’s will be provided with new details and anecdotes, both real and fictitious. Let’s wait and see.

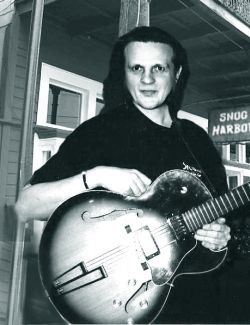

|

| Sergej Letov, Mihail Zhukov |

Before and after the perestroika, many musicians took interest in avant-garde jazz; there’s a lot to remember. We can even speak about the history of such a phenomenon as “new avant-garde jazz in Moscow”. However, the concept of “Moscow avant-garde jazz” is contradictory and paradoxical.

I believe that the main paradox of the history of Moscow, and maybe of all national avant-garde jazz is that many familiar reference marks were considerably shifted: while in the rest of the world the avant-gardists were searching for alternative ways to protest against bourgeois values of the consumer society, for our fellow nationals is was an escape, curiously enough, to the bourgeois Western perception, an attempt to join the Western civilization’s values.

It was a unique situation. The first big tours of our new-jazz musicians and first records released by Leo Feigin were intended not for the opposition, not for the social underground, not for the leftists or reds, who used to group around the avant-garde art in the rest of the world, but for enlightened common people, festival goers, consumers of ECM production (a West German record company, promoting a meditative fusion of jazz, academic music and exotic folklore – editorial comment), who were mainly interested in enrichment of their outlook and seeing the system breakdown. This was the consumer, who formed the situation of emergence of Soviet avant-garde in the West, and our performers, intentionally or unconsciously, tried to match those expectations – the expectations that people from behind the ‘iron curtain” would bring some powerful emotional and intellectual impulse to renovation.

It should be kept in mind that appearance of Vladimir Chekasin, Vyacheslav Ganelin and Vladimir Tarasov was a great event on a scale of the provincial town Vilnius, and performance of Mikhail Yudenich and Vladislav Makarov in Smolensk was just a revolution in minds… In Moscow, a huge city, the avant-garde scene could only exist as an alternative environment, as “a world of processes rather than results”, a world without stars but with communities and families. As soon as the comprehension of this special place in the society vanished or the feeling of environment was lost, music used to lose its originality and self-sufficiency. Some people could blossom out, bright records were released, and great concerts were held, but the precious stem supporting everything was getting weaker and more unreliable.

1. Time of Expectations

The Moscow jazz avant-garde originated in the 60’s-beginnning of 70’s, and we know about this period only by hearsay. They say that the legendary Gevorgyan brothers played in this style: the composer and pianist Evgeny and the contrabass player Andrey. Unfortunately, no traces of their endeavors remained by the time of perestroika. For a couple of times I listened to the joint project of Evgeny Gevorgyan with the leader of the Academic Saxophone Quarter, Lev Mikhaylov, and their performance was woeful. Probably, in the future, laurels of pioneers will be returned to them, but none of them could be imagined as the originator of the national new jazz. But when listen to Evgeny Gevorgyan’s music from “XX Century Pirates” movie, I just can’t hold back my tears. Remember the scene, when Eremenko jumps overboard and sends the pirates’ ship to the bottom?

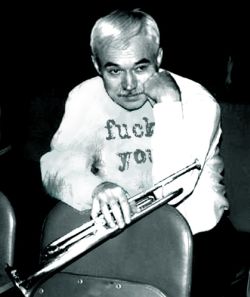

|

| Arkadij Shilkloper |

Generally, the inner attitude toward the music you’ve never heard is very strange sometimes – I noticed that reading Thomas Mann’s novel “Doctor Faustus”: description of music was very bright, though in reality (as we know) Schoenberg’s opuses do not sound as colorful and tempting as described by Mann. Rather boring.

Many our musicians could not stay indifferent to American and European free-jazz of the 60’s. The saxophonist Alexander Pishchikov, Alexei Kozlov and Igor Saulsky were obviously close to open and free forms. Progressively thinking musicians were grouping around German Lukyanov. The saxophonist Yuri Yurenkov can be considered a talented propagandist of Ornette Coleman’s ideas. The pianist Leonid Chizhik and the drummer Vladimir Vasilkov, people from Lukyanov’s toss, were playing freely in a way. Though German Konstantinovich had always considered avant-garde somewhat charlatanic and, apparently, just hated it.

In a word, many musicians one way or another touched the Coleman’s type free-jazz, but later they used act as opponents of free improvisations and free forms; alas, the place in the national music hierarchy they hurried to occupy obliged them to be critical about their juvenile experiments. Well, it was their business, but sometimes it was a shame that musicians would not see and hear what would could useful to them.

Lukyanov spent a half of his life side by side with avant-gardists. I also shared the rehearsal base at the cultural center of the Moscow Sverdlov’s factory with them. Nikolay Dmitriev and the guitarist Misha Yutkin used to organize concerts there (Yutkin was the art director of this center; he played quite moderate, non-radical music, but always welcomed much braver rock and jazz-musicians). Lukyanov was arrogant and never listened for interesting, in my opinion, phenomena, which could timely galvanize his own cooled-down mastery. It was finally understood that one couldn’t count even on a short-term cooperation with him. By the way, the bass player of “Moscow Composers’ Orchestra”, Oleg Dobronravov, used to play in Cadence, though not tool long.

As a matter of fact, Moscow was ahead of time: the local scene was similar to the modern New York Downtown – it was the synthesis of rock-music, jazz, academic experiments, noise, electronic and other genres I can’t even identify.

For instance, in the end of the 80’s, a very good, interesting, absolutely contextual, alternative, underground group called ZAiBI (“For anonymous and free art”) appeared and also gone-nowhere. On a semiprofessional (from the point of view of the Composers’ Union members), but clearly apprehensible level they tried to synthesize different arts.

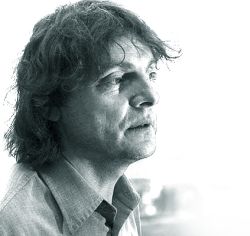

|

| Bogdan Mamonov, Kolja, Andrej Solov’ev |

On the other hand, there was such a person, very important for the Moscow underground scene, as Sergey Zharikov, and the people grouped around him and his band DK were musicians, artists, actors… All in one, it was our Rock in Opposition, Lower East Side and maybe something like a creative laboratory, formed in Great Britain around the drummer Chris Cutler and Recommended Records. The main principle was “not what, but how”, and it produced confidence in the experiment, representatives of various genres, different musical traditions. Alas! The irony of it is that all victories and achievements of the Moscow avant-garde were movements away from this fruitful environment, which was not realized in any more or less professional, bright, clearly perceived, well-structured projects.

2. The Borderline

As it happens during great social changes, on the eve of the perestroika, many people (including musicians) believed that everything was possible; indeed, many things could have been done, but the majority of the participants just didn’t see the prospects of the new synthetic art. That is why some of them took another track, shown by the jazz critic Efim Barban, who lived in Leningrad those days, the others preferred an easier and more accessible way of “explanatory” art, which led to the stages of big festivals (I don’t mention those who made business out of avant-garde). Generally, the both ways meant the departure from the very fruitful, self-contained, underground environment, where virtually all the significant participants of the Moscow avant-garde were boiling in the end of the 70’s – beginning of the 80’s – Sergey Letov, Mikhail Zhukov, the guitarist Igor Grigoryev, the multi-instrumentalist Boris Labkovsky, the guitar player Andrey Suchilin and many other people. Some of them quit music, some left the country, and some became stars.

Today many people believe that the Moscow avant-garde does not exist any more. This is not quite so. The Moscow avant-garde has not disappeared – it just took the beaten track, as it often happens. For example, there is a lot of avant-garde in Japan, but negligibly little OWN avant-garde. But how they imitate Eliot Sharp, Zorn and Willem, applying much talent and typical Japanese meticulousness! It is also true with our musicians: they have not abjured avant-garde. The situation has changed, and music has changed afterwards: before the perestroika it was in opposition to the Soviet system and the official, dull and engaged art and it was some sort of a window to Europe, but our pioneers never anathematized values of the bourgeoisie civilization unlike their Western colleagues.

Generally, many interesting things were going on in this plasma, but most of them will remain only in memoirs. Though something was fixed on video and records, but I believe that time will come and art lovers will collect the debris of this strange transient art, although many manifests of those days, which were perceived as some extremely significant events, have absolutely lost their attraction by now and have become trifling.

Those experiments made in the pre-perestroika workshops and what is considered the Moscow avant-garde now are absolutely incomparable. The music of the transient period was very special; it was based on spontaneous syncretism, and today’s avant-garde is taken to pieces: this is a show, this is an ethnic dalliance with an enlightened middlebrow, this is an attempt to approach to academic musicians, and this is multimedia art and corresponding royalties for music to theatrical and cinema production. But that art was a real breakthrough, because it was a blind search; it was created “not for anything and not for anyone”, it was unselfish – it was a program, whose creators were interested in the environment itself: somewhat shocking, not quite understandable, but a very appealing world of free art and unlimited creativity.

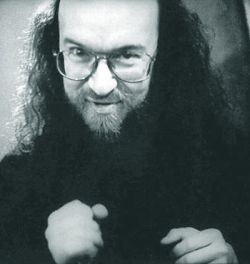

|

| Igor’ Grigor’ev |

And don’t forget about a continuous pressure, exerted on marginal musicians by the society and authorities. Some organizations persistently placed pressure on many of them, especially on people from Zharikov’s company. Maybe it was not KGB tricks, but the environment was not very comfortable; sometimes it was frightening to visit an exhibition on Bolshaya Gruzinskaya or to play at another secret gig.

Many musicians hesitated to quit their primary non-musical occupation. Letov, for example, was a chemist and worked at a research institute, but finally left the job, became a musician, graduated from Tambov cultural institute and got a job of musician. Shilkloper was rotting in the Bolshoi Theater. It was terrifying: one could easily get between grindstones of various party and Komsomol mechanisms.

3. A Place in the Sun

Everyone went through the changes in his own way. It is easier to track by concrete events. One of the brightest figures was, certainly, Sergey Letov. He was the absolute leader, and it is hard to deny. And now he remains the most consistent representative of the Moscow avant-garde, its image. Though in the very beginning, when I first met him, he was absolutely uncompromising and contacted and performed only with Bohemian artists, poets and musicians. He was different than today. I remember, how Letov and Zhukov played a short and frantic suite “Tyani-Tolkay” in 1982 – minimum pathos with maximum expressiveness.

I was lucky to see from the inside how his main project was born – TRI “O”. It so happened (and I’m proud of it) that I, not Shilkloper, was the third member of this wind ensemble together with Letov and the tuba player Arkady Kirichenko (the band was called TRI “O” later).

Letov invited me to play a small “flat gig” for foreigners, organized by Artemy Troitsky. Our music was certainly far from TRI “O” program, though we already included Oscar Pettiford’s Blues in Closet in our repertoire. Kirichenko sang a rollicking blues to Letov’s cycle pump, and Letov performed an Armenian erotic ballad a la Djivan Gasparyan. The repertoire of the familiar TRI “O” was forming this way.

I failed to stay in this band: I had no chances, because my participation supposed an inward movement, into the laboratory environment, and Letov needed a virtuoso soloist, a star, a flamboyant musician, who could excel Letov and Kirichenko both technically and by musical education. The right person was Arkady Shilkloper. Of course, his joining in was the beginning of the triumphant rise of the group, but at the same time it was the movement away from this fruitful magma, where Letov used to boil before the perestroika.

|

| Jurij Parfenov |

Such a community of so different people as TRI “O” allowed the presentation of our music on many serious scenes: it was funny, it was smart and bold. No wonder that many famous people from other artistic circles recognized the musicians. For some period, TRI “O” performed with the actor Alexander Filippenko, and it was quite different from cooperating with participants of exhibitions on Malaya Gruzinskaya. It was pure entertainment, a show. When this direction ran dry, Shilkloper left the band and, correspondingly, the brightest page of the TRI “O” history was turned, because the current line-up – the bassoon player Alexander Alexandrov, the trumpeter Yuri Parfenov and Letov – is a solid, but not very original group. Letov and his partners have a very vast experience, but the present TRI “O” is not perceived as an enlightening star on the Moscow musical horizon.

Like Letov, who was the brightest figure under the wing of Zharikov and his band DK many representatives of this informal community started searching for contacts with a wide audience, which meant a compromise and self-limitation. The saxophonist Viktor Klemeshev and the guitar player Dmitry Yanshin founded a rock-group, which later got into a more traditional groove – I mean the group Vesyolye Kartinki (Cheerful Pictures). In the beginning it was Letov’s project, playing complicated instrumental rock-music with odd rhythms and atonal improvisations a la Coleman’s “harmolodics”. But later Vesyolye Kartinki completely departed from Zharikov’s DK and turned to an ordinary blues-rock band. But the beginning was very promising; as far as I remember, Olesya Troyanskaya sang with them – people called her the Russian Janis Joplin, though she wasn’t Janis at all, but was a good avant-garde singer from the group Smeshchenie (Displacement). An interesting multi-instrumentalist, Yuri Orlov, was mixing in the same community.

4. Lukin

However, the most original, the most mythical person at the source of the Moscow jazz avant-garde was the saxophonist Viktor Lukin. He became a myth mainly thanks to his closest apprentice, the person who treated him as a saint. I mean Boris Labkovsky. Now Labkovsky, a very refined musician, is mainly performing with Rada Tsapina (Rada and Ternovnik), playing the sax and bass guitar. But in his time, when I came across him, he was a very good drummer, able to produce hundreds of sound nuances from a wracked Soviet drum kit, and he was very convincing at that. According to him, stories of Lukin’s life reminded of Buddhist jatakas…

|

| Arkadij Kirichenko |

Here’s one of such stories. Once he came to the Moskvorechye studio. He was told to learn a Coltrane’s or Parker’s solo. Lukin did not understand why. “Why Coltrane can’t learn something from me instead?” thought the musician, walking though the studio corridors. Even here, some people called jazz an art of free improvisation, not without tremulousness. But Lukin took everything for granted: freedom of expression for him was an absolute. Of course, Lukin was kept off the stage, so he had to be cunning. With a borrowed jacket and tie on, the saxophonist came to the dean’s office and promised to play at the reporting concert a paraphrase on the Russian folk song “A Birch-Tree in the Field”. With a heavy heart, the administrators gave him the green light. Lukin was playing for twenty minutes. Alone. Solo. He roared double tides, first on his knees, then lying on his back and, finally, standing on his head. “I just showed a birch-tree”, he explained, twisting his moustache and grinning. The members of the art directors had a hard time at the district party organization, and Lukin was expelled. This is how the Russian free jazz was born.

Soon Lukin left for the United States. People say that when he arrived to Washington, first of all he addressed a policeman in broken English: “How can I get to the White House?” The cop looked up and down this shaggy tramp-looking man and, without saying a word, hit him on the head with his club. Lukin realized that his free style would not hit everyone’s taste in America as well. He mainly played in the open air. He sent a postcard to his apprentice Labkovsky to Moscow with a brief note “Playing in the streets of Nu York”.

After a while Lukin moved to India, then to Nepal. Information about this period is very incomplete and fragmentary. Some said that he had joint Tigers of Liberation of Tamil Ilam, some said he got a life sentence and was put in a Nepal dungeon, others said he caught some tropical disease and died alone in terrible pangs.

Today it is hard to find out what is true or false in these stories. Lukin was just forgotten. Nobody noticed when he showed up in a Russian embassy, wishing to come back. Too much has changed since he was belching heart-rending sounds, standing on his head in a club in the suburbs of Moscow. Interest to free jazz in Moscow declined, but now we have our own White House. Cops are cops everywhere, so it is safer to buy a guidebook and find your way by yourself.

Another figure, not less distinguished than Letov and Lukin, was the drummer Mikhail Zhukov, who had his own percussion ensemble, called Uneasy Music Orchestra. Many interesting musicians played there – the percussionist Igor Zhigunov (later Megapolis), the arranger Aleksey Nechayev, future MD&C Pavlov – Aleksey Pavlov from Zvuki MU, Dima Tsvetkov, the drummer of Nicholas Copernicus. Zhukov’s orchestra was a part of the nonconformist scene, but then Sainkho appeared. Zhukov started playing the “Tuvinian card” and it all ended up as ambiguous bunch of ethnic banalities.

5. At the Junction

The Moscow avant-garde was developing at the junction of rock-music and experimental jazz. Interest in Barban’s theories led away from this too simplified scheme; they required more philosophy, metaphysics, more seriousness, Joyce, Freud, etc. Letov, for example, always reckoned himself among prophets of the new sexual revolution in music. But the most interesting experiments or events happened at the junction of avant-garde jazz and rock, as I said.

One of the examples is the guitarist Andrey Suchilin, who took Fripp’s courses, toured in Europe and played here with his project C-Major. Once Suchilin had an excellent duo with the saxophonist Alexander Voronin (in summer 1998 this excellent musician died in an accident). They played whimsical compositions with minimalism elements, skillfully transforming the famous Fripp’s cyclic conception. I still listen to some live unprofessional records left from those days.

Rai was an astonishing project of a very refined, interesting drummer, Sergey Busakhin. Busakhin began as a jazz drummer, but then he turned onto electronic noise music, and the group Rai was founded, which probably resembled British jazz-rock avant-garde, though similar projects could be found in the States, connected with Lower East Side and Californian projects such as Mr. Bungle. Busakhin played with jazzier projects, cooperated with the contrabass player Viktor Melnikov. I was lucky to play with him several times.

|

| Aleksandr Voronin |

It is rather strange, but the Moscow scene better manifests itself far away from the capital, for example, at “Unidentified Movement” festivals, organized by Sergey Karasev in Volgograd. As I already said, much of what failed to become an event in Moscow and hit the big stage was realized in the province, which showed more attention, interest and respect. Bigger things are better seen from the distance.

I played in Volgograd four or five times. I best remember a performance within a trio with Viktor Melnikov (contrabass) and Sergey Busakhin (drums). I need to say a few words about Viktor Melnikov. Unfortunately, the only record with his participation is one of the discs released by the Moscow Composers’ Orchestra, where he plays a modest role of the second bassist together with Vladimir Volkov, though he was an outstanding musician.

In the beginning of the 70’s, Viktor Melnikov represented our country at the Warsaw Jazz Jamboree, where he was impressed by the famous British trio of John Serman (baritone saxophone), Barry Phillips (contrabass) and Stuart Martin (drums). In their music he saw possibilities for implementation of ideas of the Russia avant-garde modal jazz. His numerous projects were attempts to make this dream come true. I consider the trio of Zhukov-Letov-Melnikov to be a unique ensemble with an immense potential and energy, which could develop in a phenomenon not less than Ganelin’s trio. Melnikov was an excellent saxophonist; sometimes he would take the baritone sax and played dramatic and energetic dialogs with Letov. For some time Melnikov was the music director of the jazz club at the Bauman’s Moscow Technical University. The graduates of the Bauman’s University included (earlier, of course) Evgeny Gevorgyan, Nikolay Panov, Viktor Voytov. I remember him using the famous chamber choir Gaudeamus from the same university for performing a vocal-instrument jazz-rock suite with Russian folk themes. All this was very refreshing and interesting.

At the junction of rock and jazz the groups Asphalt, Krysha (Roof), Bolshaya Krysha (Big Roof) and other projects of Igor Grigoryev emerged. This musician is also considered one of the key figures of the Moscow improvisational scene. In the beginning of the 80’s he showed himself as a well-prepared, skillful and educated jazz musician, a good connoisseur of the jazz guitar, a teacher and at the same time a very open person, who had lived a wild rock’n’roll life.

He knew very well many veterans of the Moscow rock scene, but deliberately chose the way of experimental jazz musicianship. I think that Krysha’s vinyl record (it was called “Krysha. New Music” – I still have several LPs) is still interesting, and it’s not only my opinion as a participant. Recently I had a talk with the owner of SoLyd Records, Andrey Gavrilov, and he said “What I would issue today with great pleasure is Krysha’s records, released by Melody Records”.

Grigoryev formed Asphalt back in 1987. At the start this project was developing “no wave” ideas. Grigoryev listened to a lot of such musicians as Jamaaladeen Tacuma, James ‘Blood’ Ulmer, Ronald Shannon Jackson, and took to pieces all secrets of Coleman’s “harmolodics”. He asked me to join Asphalt, but I was busy lecturing. I remember him calling one day, saying they had a very important rehearsal. I replied that I also had an important chair meeting and didn’t go. He didn’t try to persuade me any longer and took the electric violin player Dima Khanukayev. The first line-up also included Mikhail Zhukov on drums and Igor Zhigunov on the Ural bass guitar.

It was a very good line-up – an angry, energetic and very complicated music with twisted rhythms. But Dima Khanukayev left for America soon. Grigoryev attempted to engage other musicians; the pianist Artyom Blokh played in the group for some time, and with this line-up – Grigoryev, Zhukov, Blokh, Zhigunov – the band went to St. Pete in 1987 to attend a very important symposium, organized by Alexander Kan. I also was there, reading a report at the morning session, and concerts took place in the evening. Artyom Blokh was an excellent pianist, a real jazz intellectual, but he did not quite match Asphalt. He also did not get along with the leader.

|

| Aleksandr Kostikov |

Then Grigoryev attempted to engage Letov to play at a big festival of avant-garde jazz and rock, held near Moscow, in Khimki, in a huge local cultural center (playing outside of the city was quite common). I remember that Zhukov with his percussion orchestra played at the festival, as well as Srednerusskaya Vozvyshennost (Central Russian Upland), founded by the “toadstool” artists and Dmitry Alexandrovich Prigov, a very interesting group in the vein of Rock in Opposition. Grigoryev showed a variant of Asphalt with Letov. Soon people started talking about a new Letov’s project. Grigoryev was a creative, but at the same time very ambitious person. So Letov did not participate in the group any more (however, when Dmitry Ukhov persuaded the management of Melody Records to issue a disc of Asphalt, he insistently recommended Grigoryev to invite Letov for the recording, but Grigoryev was uncompromising)…

In 1988 Igor Grigoryev called me again. We went to a festival in Volgograd with a new line-up of Asphalt, including the drummer Aleksey Pavlov (he went to the festival with Zvuki Mu), the bassist Aleksey Soloviev (an interesting musician, not a relative of mine), Grigoryev and me. It was a very interesting performance; I have a video, and I believe it was fun and very refreshing.

Not only musicians contributed to the development of the Moscow avant-garde scene. Critics and organizers sometimes better and deeper understood what was going on. Igor Lobunets, who worked at Govorit Moskva Radio during its establishment, broadcasted wonderful Saturday programs, devoted to experimental music: jazz, rock, avant-garde – everything, absolutely open to anyone. By the way, it was Lobunets who recorded the famous LP by TRI “O” in the Sovremennik Theater, which later was issued by Melody Records. This record had no Shilkloper’s sweetness, no Kirichenko’s populism: it was a powerful and interesting Letov’s (!) disc, realizing the avant-garde edge of the group. Along with Krysha’s records, it is one of the key documents of that unique epoch of the Moscow avant-garde.

Besides all that, the Moscow scene cannot be imagined without people, who lived nearby and visited the city. Musicians from small provincial towns, where it was very hard to develop for avant-gardists, used to frequently visit Moscow. For some time they did not let the Moscow avant-garde scene break to pieces and decay. These included Smolensk avant-gardists Vladislav Makarov and Misha Yudenich, Eduard Sivkov and Mikhail Sokolov from Vologda, Yuri Dronov and Alexander Sakurov from Ivanovo.

6. Power of Illusions

|

| Andrej Solov’ev, Viktor Mel’nikov |

Talking about the Moscow avant-garde, it is impossible to mention big bands. It may seem funny today, but in the beginning of the perestroika, musicians wanted to unite and act as a united front. At first, just separate timid attempts were made. This process was much intensified by Sergey Kuryokhin. I remember how in 1983 the saxophonist Anatoly Vapirov, Valentina Ponomaryova and Sergey Kuryokhin played the famous concert in the Moskvorechye Cultural center, and on the next day Kuryokhin performed at the MIFI Cultural Center with a line-up, which was called Crazy Music Orchestra, not Pop-Mechanics yet. He invited there anyone he could find: Letov, the saxophonist Sergey Lukanov, “Africa” Bugayev, the bassist Dmitry Shumilin…

I was lucky to take part as well. After the concert he played with Vapirov the day before, Kuryokhin had a terrible hangover; he complained about heartache and had to take validol. In spite of this (or thanks to this) the concert was terrific. You may not believe, but even now, tuning myself before coming out on the stage, I often try to call back that concert and appeal to my inner experience, which I gained during that concert, looking for that special vibe…

This joint performance with Kuryokhin was a strong impulse to do something similar by our own. First, the omnipresent Letov took the initiative: he united us in a small orchestra, which he called Afasia. We gave a couple of concerts in the end of 1983 – beginning of 1984 in Kautchuk Cultural Center. Artyom Blokh, whom I already mentioned and who, by the way, was Kuryokhin’s cousin, played the grand piano. I remember him going frantic during one concert: he kicked away the chair, took a boxing pose and knocked out the grand piano with several smashing blows. Knocked-out keys were flying around…

Igor Grigoryev had a similar orchestra called Bolshaya Krysha. This project was specially organized to meet Misha Lobko, a very interesting French musician, a bass clarinet player (he is best known for recording with Misha Mengelberg). Lobko was going to open his own record company and, like Leo Feigin, to release our musicians, issuing a large box, similar with Document of Leo Records. He brought digital equipment, never seen here by the end of the eighties. To declare about himself, Grigoryev gathered the orchestra Bolshaya Krysha for this record specially, having invited musicians from Zhukov’s ensemble and the people he played with in Asphalt.

In my turn, I called my friends-musicians – drummers Aleksey Pavlov and Dmitry Tsvetkov, the guitar player Konstantin Baranov (later of Alliance), the keyboardist Boris Monastyrev (now known as Boris Diart), saxophonists Sergey Lukanov and Alexander Ioltukhovsky. All compositions were written by Grigoryev, skillfully inserting fragments from Asphalt, conducting the orchestra in a very peculiar way, playing guitar solos at the same time. I remember that Nikolay Dmitriyev (!) played the trombone; I have pictures taken during this performance.

I met Kolya Dmitriyev at some audiophiles’ gathering, where people exchange, sorry, speculated vinyl discs. We get along very quickly, feeling some mutual sympathy, and soon he started inviting me home. First we were just friends, listened to free jazz together, visited lectures of Leonid Pereverzev, Dmitry Ukhov and Aleksey Batashev.

Our first joint project was the magazine Delo (Affair), which we published during the perestroika. Those days there were two very impressive underground magazines – on the one hand, the very serious and interesting Kvadrat (Square), published by Barban in St. Pete, and on the other hand, there was Sergey Zharikov with the witty magazine Smorchok (Snot).

|

| Arkadij Shilkloper |

We decided to make something similar, but focused on improvisational music and jazz. I can’t judge how we succeeded, but it was very fascinating in the beginning. Everything was made up on paper of a regular format, on which we glued pictures and made collages. We took pictures and printed them as post cards in 20-30 copies and sent them to different active people, involved in organization of music events.

We sent out first ten issues, and nobody knew who we were, because all materials were unsigned. People used to tell us “Do you receive this? Some freaks have sent us this magazine…” Later Zharikov started frightening us that all of us had been already “registered there”, that he had already been dressed down for his Smorchok, and that they would surely come for us (it was the time of another campaign against underground press – editorial comment), but we did not give up. We published news, where real and fictitious events were mixed up without any explanation. We had regular columns, for example, “Blind Test”: we selected records of Russian musicians and gave them to Chekasin, Kuryokhin, Gayvoronsky and other musicians and they tried to guess or just rate them. It was fun. We published reviews of new records, concerts, events – all around the new improvisational music. For eighteen months we issued about twenty numbers, and, thank God, nobody came for us…

It is interesting to know that Nikolay Dmitriyev was the founder of the DMUT movement (Home Musicianship of Oral Tradition). People gathered at his place and everybody played numerous semiprofessional, self-made and children’s musical instruments. It was during the “port wine epoch”, in the 70’s – beginning of the 80’s. I would not say that there were many famous people there, mainly intellectuals with good musical tastes. Musicians were not much interested in taking part in such fun. But it was interesting for all of us and it reflected the spirit of those madcap and unselfish days.

7. Kings and Cabbage

The most distinguished project of the Moscow scene – Moscow Composers’ Orchestra – was founded in 1985, after experiments with Kuryokhin and Afasia. It happened soon after the first performance of Pop-Mechanics on April 14, 1984 on the stage of Moskvorechye Cultural Center (Pop-Mechanics #1 was launched in Moscow, curiously enough, under the wing of the consistent traditionalist Yuri Kozyrev). Of course, this performance produced a great impression on us. Certainly, all of us were on the stage that evening.

The basis of the Kuryokhin’s band was the orchestra of Viktor Melnikov. Melnikov cooperated with Kuryokhin many times, participating in joint projects at festivals in St. Pete, Yaroslavl and Novosibirsk. They understood each other with a half word. After that, a Moscow analog could not but appear. So it was decided to organize Moscow Composers’ Orchestra. I was making arrangements. We rehearsed in the Bauman’s University and prepared a long and powerful program.

|

| Sergej Letov, Artem Bloh |

We played it several times in 1985-86: the first performance happened in Medics’ Cultural Center on Gertsen Street (now Bolshaya Nikitskaya), where Helicon Opera is located now. Then we played in a very good large hall of the famous cultural center of Dynamo Plant at Avtozavodskaya subway station, where Sergey Zharikov was rehearsing. Alternative concerts were held there (technical services were provided by the well-known electronic and sound engineer V. Osinsky). Later the orchestra played at a festival in the cultural center of the Sverdlov’s factory, at one of the first Alternative festivals, in the very end of the 80’s. I was the band leader, and Nikolay Dmitriyev was the director.

Our first program was called “Galley’s Comet” (this comet was approaching the Earth, like in 1812); another program was called “Mandragora”. Nikolay Dmitriyev presented me to my birthday with some LP with the following dedication:

Galley’s comet flies around,

Mandragora is deep in the ground.

Soon we’ll hear Andrey growl

Form a black plastic disc with a hole…

Then we took a pause. For several years the orchestra did not play, because many people – Letov, Shilkloper, Kirichenko – started touring, spending much time abroad, enjoying their stardom, and it was difficult to involve them in democratic cooperation. Igor Grigoryev moved to the USA, settled down in Los Angeles and started working with Stan Getz, Shorty Rogers and Rodney Oakes…

But Dmitriyev and I did not stop hoping and at some moment decided to revive the Moscow Composers’ Orchestra. We decided to come around and invite a new leader from outsiders. We chose the pianist Vladimir Miller, who lived in London. We thought that he, a new and neutral person, would lead the Moscow new jazz team for some time (soon I realized that we had made a fatal mistake, but it was too late).

|

| Sergej Letov |

In the beginning everything looked fine. Miller made interesting musical scores, offered some variants for recording and soon released the first disc at Leo Records. It slightly reanimated the process in general. The thing is that orchestra management requires a lot of paperwork. Improvisation is improvisation, but it is important that the basic theme is fixed somehow. Being an orchestra, musicians cannot just play whatever they want on the basis of freedom of expression – with a large line-up this sounds very boring, transforming into a noise. Sometimes a specific compositional technique can be used, when all the bandsmen kick over the trace; it sounds powerfully, there is something amazingly wild about it. Nevertheless, using capabilities .

September, 2005 Translation from Russian from the kind sanction of the author. Author’s site: http://muzprosvet.ru The primary source in Russian http://muzprosvet.ru/journalismus.html

Leave a Reply